7. Testing-and-Integration#

7.1. Learning outcomes of this chapter#

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

Map different integration strategies to test strategies.

Describe the purpose of the different levels of testing: unit, integration, system, user acceptance, and regression.

Compare and contrast exploratory testing to systematic forms of testing.

7.2. Chapter Introduction#

In this chapter, we look at the process of building up systems from their component. The relationship between integration (or creating system builds) and testing is an important one. The order in which modules are integrated and tested can make the process of finding faults easier if a good strategy is chosen and may result in fewer latent faults [1].

The process of developing and debugging your programs, building your programs, validating and verifying your programs and testing your programs are inter-related and depend upon each other.

In general terms, a software system is a collection of programs. You may be developing a single (often referred to as a monolithic) program, or you may need to develop a suite of programs that must work together to achieve a common goal. We will use the word “system” to mean either a single program or a collection of programs.

The development of a system typically follows a process that involves requirements, design, implementation and testing phases. The process also typically uses various methods for validating and verifying the documents, plans, programs and other artifacts that are developed in each phase. This is where the various life-cycles and techniques from the Software Processes and Management subject are used.

7.3. Integrating the System#

In the process of designing a system, you will have decomposed your system into modules, packages or classes. If the system is complicated then you may have decomposed each module into sub-modules and so on.

Integrating your system refers to putting the modules, packages or classes together to create subsystems, and eventually the system itself. Generally speaking, integration and testing go together. Good integration strategies can give help you to minimise testing effort required. Poor integration strategies generally cause more work, and lead to lower quality software.

Normally, a system integration is organised into a series of builds. Each build combines and tests one subset of the modules, packages or objects of the system.

The aim for most integration strategies is to divide the modules into subsets based on their dependencies. Typical build strategies then try and integrate all those modules with no dependencies first, the modules that depend on these second, and so on. Here are some examples of integration strategies.

7.3.1. The Big-bang Integration Strategy#

The Big-Bang method involves coding all of the modules in a sub-system, or indeed the whole system, separately and then combining them all at once. Each module is typically unit tested first, before integrating it into the system. The modules can be implemented in any order so programmers can work in parallel.

Once integrated, the completely integrated system is tested. The problem is that if the integrated systems fails a test then it is often difficult to determine which module or interface caused the failure. There is also a huge load on resources when modules are combined (machine demand and personnel).

The other problem with a Big-Bang integration strategy is that the number of input combinations becomes extremely large — testing all of the possible input combinations is often impossible and consequently we there may be latent faults in the integrated sub-system

7.3.2. A Top-Down Integration Strategy#

The top-down method involves implementing and integrating the modules on which no other modules depend, first. The modules on which the these top-level modules depend are implemented and integrated next and so on until the whole system is complete.

The advantages over a Big-Bang approach are that the machine demand is spread throughout integration phase. Also, if a module fails a test then it is easier to isolate the faults leading to those failures. Because testing is done incrementally, is is more straightforward to explore the input for program faults.

The top-down integration strategy requires stubs to be written. A stub is an implementation used to stand in for some other program. A stub may simulate the behaviour of an existing implementation, or be a temporary substitute for a yet-to-be-developed implementation.

7.3.3. The Bottom-Up Integration Strategy#

The bottom-up method is essentially the opposite of the top-down. Lowest-level modules are implemented first, then modules at the next level up are implemented forming subsystems and so on until the whole system is complete and integrated.

This is a common method for integration of object-oriented programs, starting with the testing and integration of base classes, and then integrating the classes that depend on the base classes and so on.

The bottom-up integration strategy requires drivers to be written. A driver is a piece of code use to supply input data to another piece of code. Typically, the piece modules being tested need to have input data supplied to them via their interfaces. The driver program typically calls the modules under test supplying the input data for the tests as it does so.

7.3.4. A Threads-Based or Iterative Integration Strategy#

The threads-based integration method attempts to gain all of the advantages of the top-down and bottom-up methods while avoiding their weaknesses. The idea is to is to select a minimal set of modules that perform a program function or program capability, called a thread, and then integrate and test this set of modules using either the top-down or bottom-up strategy.

Ideally, a thread should include some I/O and some processing where the modules are selected from all levels of the module hierarchy. Once a thread is tested and built other modules can be added to start building up a complete the system.

This idea is common in agile methodologies. Threads are focussed on user requirements, or user stories. Given a coherent piece of functionality from a set of user requirements, we build that small piece of functionality to deliver some value to the user. However, this is NOT an integration strategy on its own: we will still have to bring together parts of this as we go, using top-down and bottom-up strategies.

7.4. Types and Levels of Testing#

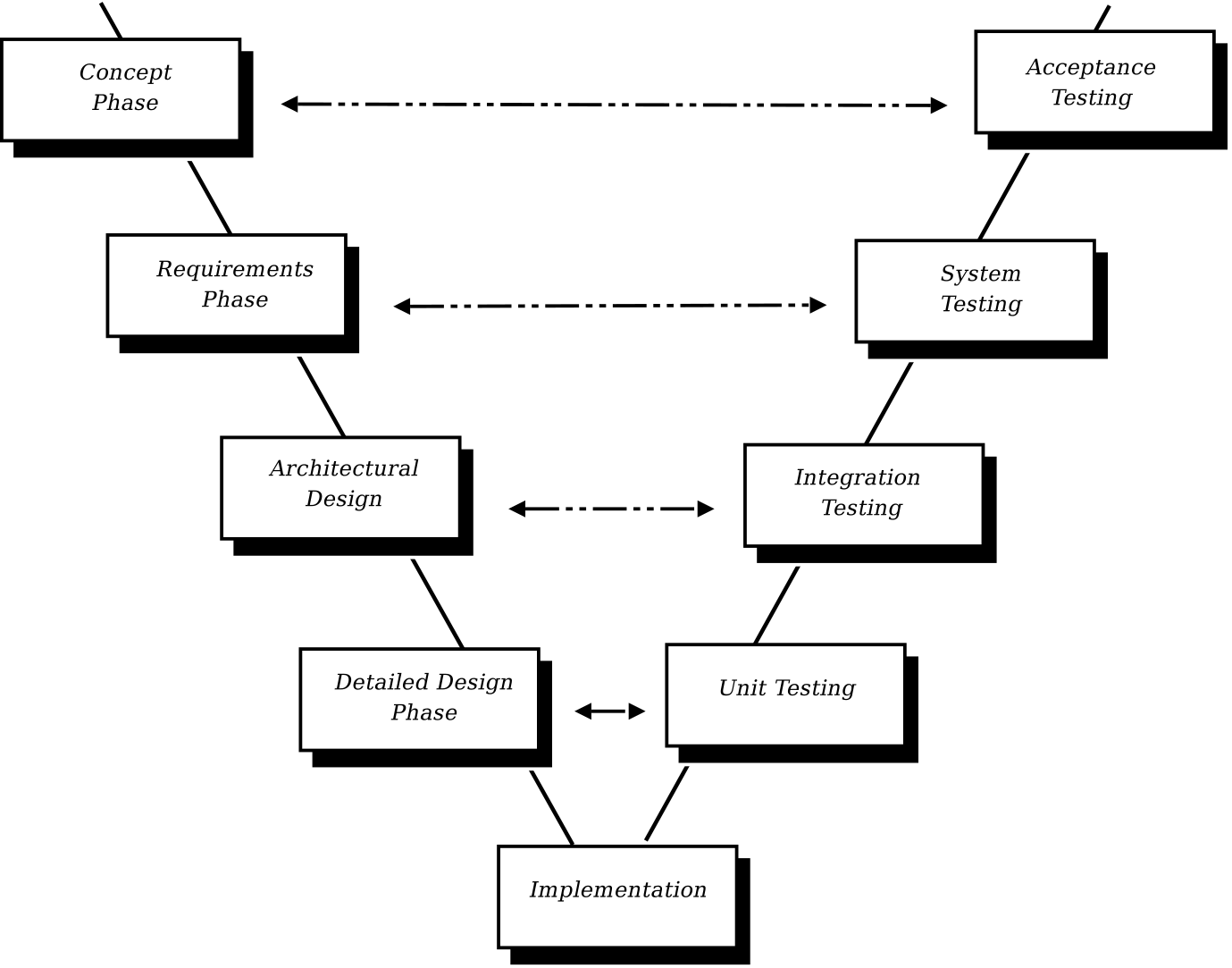

There are various types of testing that systems typically undergo. Each type of testing is aimed at detecting different kinds of failures and making different kinds of measurements. Figure 7.1 is a representative diagram that shows how each type of testing corresponds to a stage in the development[^2].

Figure 7.1: A simplified view of the relation between testing levels and development artifacts.

7.4.1. Unit Testing#

The first task in unit testing is to work out exactly what a unit is for the purpose of testing. In most cases, a unit is a module: a collection of procedures or functions that manipulate a shared state. In these cases, the module is tested as a whole, because changes in one procedure can effect others. In other cases, a unit is a single procedure or function. In these cases, the only inputs and outputs are parameters and return values — there is no state.

Units, if they are functions or classes, are tested for correctness, completeness and consistency. Unit testing measures the attributes of units. They can be tested for performance but almost never for reliability; units are far too small in size to have the statistical properties required for reliability modelling.

If each unit is thoroughly tested before integration there will be far fewer faults to track down later when they are harder to find.

7.4.2. Integration Testing#

Integration testing tests collections of modules working together. Which collection of modules are integrated and tested depends on the integration strategy. The aim is to test the interfaces between modules to confirm that the modules interface together properly. Integration testing also aims to test that subsystems meet their requirements.

Integration tests are derived from high level component designs and requirements specifications.

7.4.3. System Testing#

System testing test the entire system against the requirements, use cases or scenarios from requirements specification and design goals. Sometimes system testing is broken down into three groups of related testing activities:

Definition

System Functional Test: tests the entire system against the functional requirements and other external sources that determine requirements such as the user manual.

System Performance Test: test the non-functional requirements of the system for example, the load that the system can handle, response times and can test usability (although this latter testing is more like a survey than what we would call an actual test).

User Acceptance Test: is a set of tests that the software must pass before it is accepted by the clients. This is typically a form of validation, whereas testing against the specification is a form of verification.

7.4.4. Regression testing#

Programs undergo changes but the changes do not always effect the entire program. Rather certain functions or modules are changed to reflect new requirements, system evolution or even just bug fixes. History shows that, after making a change to a system, testing only the part of the system that has changed is not enough. A change in one part of a system can effect other parts of the system in ways that are difficult to predict. Therefore, after any change, the entire test suite of a system must be run again. This is called regression testing.

Regression testing is one of the key reasons for wanting to be able to execute test suites automatically. To test an entire system by hand is costly even for the smallest of systems, and infeasible for many others.

7.4.5. Exploratory testing#

“Exploratory testing is simultaneous learning, test design, and test > execution.” – James Bach, Exploratory Testing Explained.

Exploratory testing is a form of unstructured testing. It is done typically by experienced testers, preferably with some domain knowledge about the application. All they do is explore the software, using their experience from years of software engineering and what they have learnt about the piece of software during their exploratory testing to find faults.

It is typically conducted at a system level (but not always), simply by having people sit and explore the application, trying out different parts, observing what happens, and then repeating. It aims to exploit human insight to find faults. By exploring the application, the human tester gains insight that they could not gain by just writing tests.

Exploratory testing has several advantages over other types of structured testing. First, the knowledge gained by the tester during the testing process can lead to them understanding the requirements better than someone doing structure testing, so they may think of things that they wouldn’t have otherwise. Second, structured tests require both a test input and an expected output. So, the tester will be focused on the test output, and may completely ignore other things that are going on. Consider a web application, in which a tester executes a test, and looks at a specific field to get the actual output to compare to the expected output. They are less likely to notice other anomalies on the page compared to an exploratory tester.

It also have disadvantages. First, it does not really offer any type of structure around the testing, such as how to maximise chances of finding faults. Second, it is difficult to repeat, and difficult to run regression tests, because we do not really record what is happening.

Exploratory testing is best used in combination with structured techniques. Although it is less scientific in the way test selection and execution is done, its advantage is the use of human insight to find faults.