8. Security Testing#

8.1. Learning outcomes of this chapter#

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

Discuss the purpose of security testing.

Explain the potential security implications (in terms of integrity, confidentiality, availability, arbitrary code execution etc.) of security faults

Explain the relative strengths and weaknesses of random fuzzing vs mutation based fuzzing vs generation based fuzzing

Choose (and justify) which security testing technique (random fuzzing, mutation based fuzzing, generation based fuzzing, or some combination) is most appropriate for testing a particular software component

Explain the security implications of undefined behaviour in C code

Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of using a memory debugger to check for memory errors, and undefined behaviour sanitizers to check for undefined behaviour

8.2. Chapter Introduction#

In this chapter, we will look at a few systematic and automated approaches to testing security of systems. Specifically, we will look at three different ways of penetration testing.

Penetration testing (or pentesting) is the process of attacking a piece of software with the purpose of finding security vulnerabilities. In practice, pentesting is just hacking, with the difference being that in pentesting, you have the permission of the system owners to attack the system.

In other words, penetration testing is hacking with permission.

One way to perform penetration testing is to just try out a whole load of tricks that have worked before. For experienced pentesters, this is an excellent and fruitful approach; and in fact, many people make their career out of intelligently trying to break systems. However, this is exceedingly difficult to teach in a few week period off a university subject. Instead, in this chapter, we are going to focus on automated pentesting, which is generally called fuzzing or fuzz testing, which is a systematic and repeatable approach to pentesting, and one which is used by many great penetration testers.

8.3. Introduction to Penetration Testing#

First, some terminology. The aim of penetration testing is to find vulnerabilities. A vulnerability is a security hole in the hardware or software (including operating system) of a system that provides the possibility to attack that system; e.g., gaining unauthorised access. Vulnerabilities can be weak passwords that are easy to guess, buffer overflows that permit access to memory outside of the running process, or unescaped SQL commands that provide unauthorised access to data in a database.

Example 66

As an example of an SQL vulnerability, consider a request that allows a user to lookup their information based on their email address via a textbox, resulting in the following query to a database:

SELECT * FROM really_personal_details WHERE email = ’$EMAIL_ADDRESS’

in which $EMAIL_ADDRESS is the text copied from the text box.

If the text myemail@somedomain.com is entered, then this works fine. However, if the user is aware of such a vulnerability, they may instead enter: myemail@somedomain.com’ OR ’1=1 (note the unopened and unclosed quotation marks here). If the developers have not been careful, this may result in the following query being issued:

SELECT * FROM really_personal_details WHERE email = ’myemail@somedomain.com’ OR ’1=1’

The WHERE clause evaluates to \(true\), and therefore, the user will be able to gain unauthorised access to all data in the table, including that of other users.

Buffer overflows are another common security vulnerability. These occur when data is written into a buffer (in memory) that is too small to handle the size of the data. In some languages, such as C and C++, the additional data simply overwrites the memory that is located immediately after the buffer. If carefully planned, attacker-generated data and code can be written here.

Example 67

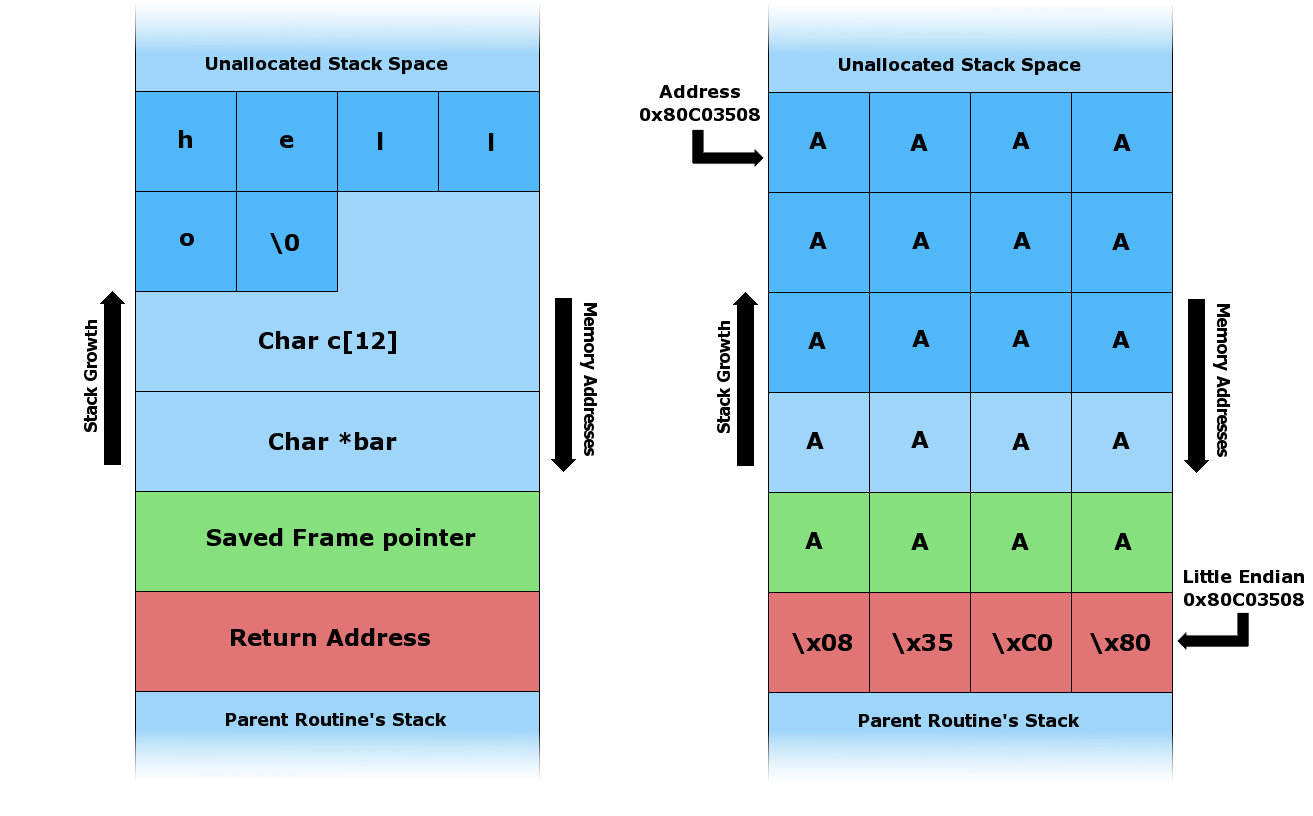

Consider the following example of a stack buffer overflow[1].

The following C program takes a string as input, and allocates it to a buffer 12 characters long:

void foo (char *bar)

{

char c[12];

strcpy(c, bar); // no bounds checking

}

int main (int argc, char **argv)

{

foo(argv[1]);

}

Now, consider the two cases in Figure 9.1[2]. On the left is the case where the input string, hello\0, is small enough to fit into the buffer. The frame pointer and return address for the foo function sit next to the buffer in memory. On the right side is an example where the input string, AA...\x08\x35\xC0\x80, is longer than the buffer. This writes over the frame pointer and the return address. Now, when foo finishes executing, the execution will jump to the address specified in the return address spot, which is at the start of char c[12]. In this case, the contents of char c[12] is meaningless, but in an attack, the string would contain payload that could be a malicious program, which would have privileges equivalent to the program being executed; e.g., it could have superuser/admin access.

Figure 9.1: An example of expect buffer usage (left) and overflow (right)

Clearly, there are many ways to try to reduce the chance such attacks: defensive programming that checks for array bounds, using programming languages that do this automatically, or finding and eliminating these problems. We can find these problems using reviews and inspections, letting hackers find them for us (not recommended), or using verification techniques.

In this chapter, we look at verification techniques, specifically, fuzz testing.

Definition

Fuzz testing (or fuzzing) is a (semi-)automated approach for penetration testing that involves the randomisation of input data to locate vulnerabilities.

Typically, a fuzz testing tool (or fuzzer) generates many test inputs and monitors the program behaviour on these inputs, looking for things such as exceptions, segmentation faults, and memory leaks; rather than testing for functional correctness. Typically, this is done live: that is, one input is generated, executed, and monitored, then the next input, and so on.

We will look at three techniques for fuzzing:

Random testing: tests generated randomly from a specified distribution.

Mutation-based fuzzing: starting with a well-formed input and randomly modifying (mutating) parts of that input

Generation-based fuzzing: using some specification of the input data, such as a grammar of the input.

8.4. Random Testing#

Random testing is one approach to fuzzing. In random fuzzing, tests are chosen according to some probability distribution (possible uniform) to permit a large amount of inputs to be generated in a fast and unbiased way.

8.4.1. Advantages#

It is often (but not always) cheap and easy to generate random tests, and cheap to run many such tests automatically.

It is unbiased, unlike tests selected by humans. This is useful for pentesting because the cases that are missed during programming are often due to lack of human understanding, and random testing may search these out.

8.4.2. Disadvantages#

A prohibitively large number of test inputs may need to be generated in order to be confident that the input domain has been adequately covered.

The distribution of random inputs simply misses the program faults (recall the Pareto-Zipf principle from Chapter 1).

It is highly unlikely to achieve good coverage.

The final point deserves some discussion. If we take any non-trivial program and blast it with millions of random tests, it is unlikely that we will achieve good coverage, where coverage could be based on any reasonable criteria (control-flow, mutation, etc.).

Consider the following example, in which we have a “fault” at line 7 where the program unexpectedly aborts.

1. void good_bad(char s[4]) {

2. int count = 0;

3. if (s[0] == 'b') count++;

4. if (s[1] == 'a') count++;

5. if (s[2] == 'd') count++;

6. if (s[3] == '!') count++;

7. if (count > 3) abort(); //fault

8. }

This program will only fail on the input “bad!”. Using random testing, random arrays of four characters will be generated, but encountering the fault at line 7 is highly unlikely. Since each char data type (in C programming lanague) occupies 8 bit in the memory, the probability of randomly generating the string “bad!” requires us to randomly choose ‘b’ at index 0 (probability of 1 in \(2^{8}\), ‘a’ at location 1 (probability of \(1\) in \(2^{8}\)), etc., leaving us with the probability of \(1\) in \(2^{32}\) that the code will be executed. In fact, almost every randomly generated test will execute false for every branch.

While this example is a fabricated example, such cases are common place in real programs. For example, consider any branch of the form x == y (unlikely that x and y will have the same value). Or, more interestingly, consider the chance of randomly generating a correct username and password to get into a system, or generating the correct checksum for a packet of data that is received. This latter case is common in security-critical applications: only if we have the correct checksum, we can “do something interesting”:

1. boolean my_program(char [] data, int checksum)

2 {

3. if (calc_checksum(data) == checksum) {

4. //do something interesting

5. return true;

6. }

7. else {

8. return false;

9. }

10. }

In cases such as this, a random testing tool will likely spend most of its time just testing the false case over and over, which is not particularly useful.

A standard way to address this is to (if possible) measure the code coverage achieved by your tests after a certain amount of time, and look for cases like these. Then, modify your random testing tool to first send some data with a correct checksum, and then use random testing for the remainder of inputs. Rinse and repeat.

8.5. Mutation-based Fuzzing#

Mutation-based fuzzing is a simple process that takes valid test inputs, and mutates small parts of the input, generating (possibly invalid) test inputs. The mutation (not to be confused with mutation analysis discussed in Section Mutation Analysis) can be either random or based on some heuristics.

As an example, consider a mutation-based fuzzer for testing web servers[3]. A standard HTTP GET request for the index page could be a valid input:

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1

From this, many anomalous test inputs, which should all be handled by the server, can be generated by randomly changing parts of that input:

AAAAAA...AAAA /index.html HTTP/1.1

GET ///////index.html HTTP/1.1

GET %n%n%n%n%n%n.html HTTP/1.1

GET /AAAAAAAAAAAAA.html HTTP/1.1

GET /index.html HTTTTTTTTTTTTTP/1.1

GET /index.html HTTP/1.1.1.1.1.1.1.1

One can imagine a simple program being set up to generate such inputs and deliver them to a web server.

As an example of a more heuristic-based mutation fuzzer, consider a text field in a web form in which a user enters their email address, as in Example 66. Attacks such as those presented are common, so an heuristic mutation fuzzer will add targets such as that to fields, instead of random data. So, a valid input such as:

'myemail@somedomain.com'

could be mutated to things such as:

'myemail@somedomain.com' OR '1=1'

'myemail@somedomain.com' AND email IS NULL

'myemail@somedomain.com' AND username IS NULL

'myemail@somedomain.com' AND userID IS NULL

These last three attempt to guess the name of the field for the email address. If any of these give a valid response, we know that we guess the name of the field correctly; otherwise a server error will be thrown.

8.5.1. Advantages#

The main advantages of fuzzing are compared to random testing are:

It generally achieves higher code coverage than random testing. While issues such as the checksum issue discussed earlier still occur, they often occur less of the time if the valid inputs that are mutated have the correct values to get passed these tricky branches. Even though the mutated tests may change these, some will change different parts of the input, and the e.g., checksum will still be valid.

8.5.2. Disadvantages#

The success is highly dependent on the valid inputs that are mutated.

It still suffers from low code coverage due to unlikely cases (but not to the extent of random testing).

8.5.3. Tool support#

There are many tools to support mutation-based fuzzing.

Radamsa (akihe/radamsa) is typically used to test how well a program can withstand malformed and potentially malicious inputs. It works by reading sample files of valid data and generating interestringly different outputs from them.

zzuf (http://caca.zoy.org/wiki/zzuf) is a commonly-used tool for “corrupting” valid input data to produce new anomaly tests. It uses randomisation, and has controllable properties such as how much of the input should be changed for each test.

Peach (http://www.peachfuzzer.com/) is a well-known fuzzer that supports mutation fuzzing, and has reached a level of maturity that make it applicable to many projects.

8.6. Generation-based Fuzzing#

Generation-based fuzzers (or intelligent fuzzers) typically generate their own input from such existing models, rather than mutating existing input (although many tools combine the two approaches).

Typically, generation-based fuzzers have some information about the format of the input that is required; for example, a grammar of the input language (e.g., SQL grammar), knowledge of the file format. Using this knowledge, a generated-based fuzzer can create inputs that preserve the structure of the input, but it can randomly or heuristically modify parts of the input based on that knowledge. Therefore, instead of randomly modifying parts of a string representing an SQL query, it can produce syntactically-correct SQL, but with random data within that structure.

Further to this, by knowing the input protocol and the interactions that are required, a generation-based fuzzer can more intelligently select inputs. For example, by knowing a protocol for a web server, it can behave as a true web client would, allowing generation of correct, dynamic responses to server responses, rather than just random data.

In essence, the strategies applied, such as which parts to change and how fine-grained the changes are, affect the “intelligence” of the fuzzer.

Example 69

As an example, consider generating a HTTP POST call with a SOAP action:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: unimelb.edu.au

Content-Type: text/xml; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 372

SOAPAction: "http://wheverer.com/somewhere"

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<soap:Envelope xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"...

<soap:Body>

<firstName>A name</firstName>

<lastName>Another name</lastName>

<paramsXML>param 1</paramsXML>

</soap:Body>

</soap:Envelope>

A mutation-based fuzzer will take an input such as this and randomly modify parts of it; for example, by replacing some random characters. In most cases, this would result in a query that cannot be parsed by the server. Non-parsable inputs can be valuable for testing the parser, but we want to also test other parts.

A generation-based fuzzer, on the other hand, would know the HTTP and SOAP protocols, so would first generate the skeleton for a parsable query, and then generate the values in between the tags of the SOAP query (randomly or heuristically). For example, it may randomly change the value in the firstName tag to a much longer string. This would result in a SOAP query that is longer than specified in the Content-Length HTTP parameter (372 chars), perhaps resulting in a case where the SOAP query overflows the buffer that is allocated — presumably 373 chars (although one would hope that the server is using a library that does not do this!).

8.6.1. Advantages#

Knowledge the input protocol means that valid sequences of inputs can be generated that explore parts of the program, thus generally giving higher coverage.

8.6.2. Disadvantages#

Compared to random testing and mutation fuzzing, it requires some knowledge about the input protocol.

The setup time is generally much higher, due to the requirement of knowing the input protocol; although in some cases, the grammar may already be known (e.g., XML, RFC).

8.6.3. Tool support#

Peach(http://www.peachfuzzer.com/), which is mentioned also at a mutation fuzzer, supports both mutation and generation-based fuzzing. For smarter generation-based fuzzing, it also monitors feedback sent to it via network protocols (for fuzzing e.g., web servers) to intelligent select new tests.

8.7. Memory Debuggers#

A memory debugger is a tool for finding memory leaks and buffer overflows. Memory debuggers are important in fuzzing, especially in languages with little support for memory management.

The reason why memory debuggers are important is because anomalies such as buffer overflows are difficult to observe using system behaviour. For example, consider the stack buffer overflow presented earlier in this chapter. If the overflow is just by a few characters, it would be difficult to detect unless that particular part of memory is accessed again, which may not be the case.

Generally, memory debuggers monitor looking for four issues:

Uninitialised memory: references made to memory blocks that are uninitialised at the time of reference.

Freed memory: reads and writes to/from memory blocks that have been freed.

Memory overflows: writes to memory blocks past the end of the block being written to.

Memory leaks: memory that is allocated but no longer able to be referenced.

Memory debuggers typically work by modifying the source code at compile type to include specific code that checks for these issues; for example, by keeping track of a buffer size, and then inserting code directly before a write to check whether the memory being written is larger than the target buffer.

8.7.1. Performance Cost#

While monitoring for these properties is useful, it is generally at a high performance cost. The overhead of keeping track of the allocated memory, plus the checks made, is expensive. For example, programs running using the well-known Valgrind tool run between 20-30 times slower than with no memory debugging.

8.7.2. Tool Support#

Valgrind[4] (and its tool memcheck) is a well-known open-source memory debugger for Linux, Mac OS, and Android. It works by inserting monitoring code directly into the source, and replaces the standard C memory allocation tools (e.g., alloc, malloc) with its own implementation that monitors references and memory block sizes, etc.

Rational Purify[5] is a commercial memory debugger for Linux, Solaris, and Windows.

8.8. Undefined Behaviour#

Buffer overflows are a form of undefined behaviour: something that a program does that causes its future behaviour to be unknown. It might continue working or it might do something totally unpredictable, such as executing attacker-supplied code in the case of a successful remote code execution attack.

Programming languages like C define many forms of undefined behaviour, besides buffer overflows. Examples of undefined behaviour in C include:

Dividing by 0

Dereferencing a NULL pointer

Overflowing a signed integer

Underflowing a signed integer

plus many more.

Testing for undefined behaviour, as with buffer overflows, requires special tool support. This is because the behaviour a program exhibits when performing an operation involving undefined behaviour cannot be relied upon. Compilers use this fact when optimising programs which can sometimes lead to very surprising results.

As an example, consider the following program signed_overflow.c:

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main(const int argc, const char * argv[]){

int32_t x, y;

if (argc < 3){

fprintf(stderr,"Usage: %s num1 num2\n",argv[0]);

exit(1);

}

x = atoi(argv[1]);

y = atoi(argv[2]);

if (y <= 0){

return 0;

}

if (x + y < x){

printf("Overflow happens!\n");

}

return 0;

}

It reads two integers \(x\) and \(y\) given as command line arguments. If the second one, \(y\), is positive, it then tries to test whether adding them together would cause overflow. It does so by checking whether \(x + y\) is less than \(x\). Given that \(y\) is known to be positive, this should happen only if overflow occurs when they’re added together.

The program behaves as expected when compiled (under Clang 7.3.0) with no optimisation:

$ clang -O0 signed_overflow.c -o signed_overflow

$ ./signed_overflow 2147483647 10

Overflow happens!

$

Let’s see what happens, however, when compiled with even the most mild optimisation level:

$ clang -O1 signed_overflow.c -o signed_overflow

$ ./signed_overflow 2147483647 10

$

Surprisingly, the program doesn’t print “Overflow happens!”.

While this behaviour might seem odd, the program has been legally compiled: signed overflow is undefined behaviour. Therefore, in any situation where the original program is guaranteed to perform undefined behaviour, the compiler is allowed to make it do anything it wants. In this case, the compiler has chosen to have the program do the thing that speeds up the program the most. Specifically, it has chosen to entirely omit the section of the program that does:

if (x + y < x){

printf("Overflow happens!\n");

}

Whenever this bit of code doesn’t perform undefined behaviour (i.e. doesn’t cause signed overflow), it is equivalent to doing nothing. On the other hand, whenever it does perform undefined behaviour, the compiler is allowed to have the program do whatever it wants. Thus removing this section of code is entirely legal: in all cases where undefined behaviour doesn’t occur the program behaves identically.

In general, a compiler is allowed to perform any transformation on a program so long as it ensures that the program’s behaviour remains unchanged in all cases where it doesn’t exhibit undefined behaviour.

Bugs similar to the one in the program above have led to vulnerabilities in Linux kernel drivers when the compiler has optimised away an overflow test of the above form that was being used to guard against accessing a buffer out-of-bounds.

Numerous articles exist online that detail how to rewrite overflow checks like the one in the faulty program above to ensure that they correctly check for over or underflow while avoiding undefined behaviour.

The unpredictability of how a program will behave when performing undefined behaviour means that undefined behaviour is important to test for. However, for the same reason, testing for undefined behaviour requires special help from the compiler. Essentially, the compiler produces a program that includes checks to ensure that execution is halted with an error whenever undefined behaviour is about to occur.

As with memory debuggers, these checks necessarily incur some performance overhead.

8.8.1. Tool Support#

The Clang C compiler provides options for compiling code to enable it to be tested for undefined behaviour. With these options turned on, Clang builds programs so that they generate an error whenever they perform undefined behaviour, as shown in the following example.

$ clang signed_overflow.c -o signed_overflow \

-fsanitize=undefined-trap -fsanitize-undefined-trap-on-error

$ ./signed_overflow 2147483647 10

Illegal instruction: 4

$

Here we see that the Illegal instruction error is generated when signed overflow occurs.