5. Testing Modules#

5.1. Learning outcomes of this chapter#

At the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

Discuss the impact that observability and controllability have when testing modules.

Construct a finite state automaton from the specification of a module.

Derive a set of test sequences that achieve the different coverage criterion of a finite state automaton.

Derive a set of test sequences from a finite state automaton that intrusively and non-intrusively test the module.

Describe the pros and cons of polymorphism and inheritance in testing object-oriented programs.

Derive a test suite that takes advantage of inheritance and counteracts the problems of polymorphism.

5.2. Chapter Introduction#

In the previous chapters, we have discussed how to select test inputs to maximise the chances of uncovering faults in a program. Examples in these chapters have been single functions, with only parameters as input, and return values as output. In this chapter, we discuss the testing of program with state; that is, testing modules. Modules present some different problems with regards to testing when compared to single functions.

5.3. State and Programs#

During the years proceeding the wide-spread adoption of third-generation programming languages, computer programs started becoming more and more complex. Practitioners realised that, instead of allowing any part of a program to manipulate any part of data, if access to data was provided via a clear and unambiguous interface made up of functions on that data, then complex program could be understood more readily.

Typically, the data, called the state, is manipulated and accessed via a collection of operations on that state. Collectively, these are referred to as a module [1]. Using modules enforces a separation of interface and implementation, allowing programmers to think of these collections of operations as a black box. Specific details about the data is hidden from the user of the module, and a change in the underlying data structure has no impact on the program that uses it as long as the interface remains the same.

Operations are meaningless when separated from their state and treated in isolation. For example, an operation may require the module to be in a specific state before it can be executed, and that state can only be set by another operation (or combination of operations) in the module.

Object-oriented programs are special classes of state-based programs, in that multiple instances of the data can be created.

5.4. Testability of State-Based Programs#

Recall from Section Testability that the testability of a program is defined by the observability of the program, and the controllability of the program. State-based programs present some issues with regards to these two measures, even for APIs.

For example, consider a module that allows the manipulation of and access to a stack. The operations of the class allow us to push an element on to the stack, view the top of the stack, pop the top element from the stack, and check whether the stack is empty. The specification of the class is allows:

Initially, the stack is empty — it contains no elements. When created, the calling program determines a maximum size for the stack, passed as a parameter to the constructor.

An element can be pushed onto the stack if the size of the stack is not already equal to the maximum size, as determined when initialised. If full, pushing another element will result in the exception

StackFullException.

The top element of the stack can be popped from the stack provided that the stack is not empty. Pushing an element and then popping the stack will result in the stack before pushing. If the stack is empty, popping will result in the exception

StackEmptyException.

The calling program can see the value of the top of the stack, but no other parts of the stack. If the stack is empty, peeking at the top of the stack will result in the exception

StackEmptyException.

Finally, the stack can be checked to see if it is empty, and can be checked to see if it is full. These operations allowing the calling program to avoid exceptions.

Figure 5.1 shows an implementation of such a module in Java, in which the stack has a maximum size, which is determined by the calling program when creating the stack data type. The variables prefixed with an underscore (_) as those that are encapsulated by the class, and are not directly controllable or observable.

public class Stack

{

private object _stack[];

private int _maxsize = 0;

private int _top = 0;

public void Stack(int maxsize)

{

_maxsize = maxsize;

_top = 0;

_stack = new Object[maxsize];

}

public void push(Object n)

throws StackFullException

{

if (_top == _maxsize)

throw new StackFullException();

else {

_stack[_top] = n;

_top++;

}

}

public void pop()

throws StackEmptyException

{

if (_top =< 0)

throw new StackEmptyException();

else

_top--;

}

public Object top()

throws StackEmptyException

{

return _stack[_top];

}

public boolean isEmpty()

{

return (_top == 0);

}

public boolean isFull()

{

return (_top == _maxsize);

}

}

Figure 5.1: A Java stack class

Using the techniques discussed in the previous chapters, we can derive some test cases to test the operation that pushes an element from the stack. Any good test suite will include at least equivalence classes for an empty stack, and a stack with at least one element. After selecting values from these equivalence classes, we can derive the executable test cases.

However, access to the stack data is hidden behind the interface. The push operation does not take a parameter for the stack, meaning that the push operation cannot be controlled via its interface. Furthermore, once an element is pushed onto the stack, we cannot directly observe the value of the stack. Therefore, the operations as part of the stack module are not easily controllable or observable.

This reduction in controllability and observability means that unit testing in isolation is not possible for the operations of the stack module. In cases such as this, the other operations that make up the module may be required to test an operation, so we have a case in which unit testing and module testing can be considered as the same activity.

One way around these testability issues is to intrusively test the module. That is, the tester modifies the program code to give access to the data type that is hidden, therefore breaking the information hiding aspect of the module. The program is tested, and the data type is hidden again. This has serious drawbacks:

it does not test the implementation that is to be used, but an altered version of it;

if the underlying data type in the module changes, then the tests must be changed as well; and

it ignores the fact that operations acting on the same data as inherently linked, and must be tested together.

One could argue that the inter-dependencies could be tested as well, but with modules such as the stack class, the high-level of dependency between operations implies that testing an operation in isolation would give us little benefit.

Rather than intrusively testing the module, we use a non-intrusive method: we use the operations defined by the module to set the state of the module to test value that we want, perform the necessary test, and then use the operations again to query the result of the test. In the example of the stack class, to test the behaviour of pushing an element onto a stack containing one element, we first push an element onto an empty stack using the push (setting up the state for our test), then push another element for our test, then use the top and pop operations to see the state of the module.

Note that many object-oriented languages provide us with constructs that are somewhat in between intrusive and non-intrusive testings. For example, in the Java programming language, variables inside classes can be declared as protected, which means that if we can inherit the class, then we can access the variables in the class. This allows us to passively observe the values of variables without changing the module itself. Other tools provide non-intrusive ways to observe data, such as inserting breakpoints in programs, and allowing the tester to observe the state of the program at that breakpoint.

5.5. Unit Testing with Finite State Automata#

The way that many modules, especially those that implement abstract data types, are abstracted is to envisage them as finite state automata.

Definition 45

A finite state automaton (FSA) or finite state machine is a model of behaviour consisting of a finite set of states with actions that move the automata from one state to another.

With regards to a module, each state in a FSA corresponds to a set of states in the module it is modelling. The transitions between states correspond to the operations in the module. Transitions can be prefixed with predicates specifying the preconditions that must hold for them to take place.

FSAs are useful for modelling behaviour of programs, and can be used to derive test cases for such programs. The states of the automaton derived from subsets of the states of the data encapsulated in the module, and the transition of the automaton are the operations of the module. Test cases are selected to test sequences of transitions in this automaton.

5.5.1. Constructing a FSA#

To construct a finite state machine, we perform the following steps.

Step 1: identify the states of the FSA. Each state in the FSA corresponds to a set of states in the module. Intuitively, we want to consider states with same effect on operations as being equivalent and collect them together into a single FSA state. The situation is analogous to the situation in equivalence partitioning where every element of an equivalence class has the same chance of finding an error. Therefore, we use the techniques described in the previous chapters to derive the states that we want to test.

Step 2: identify which operations are enabled in a state and which operations are not enabled in a state — an operation is enabled if it can be called safely without error in a given state.

For example, the

popandtopoperations are not enabled if the stack is empty, and thepushoperation is not enabled if the stack is full.From this information, we identify the start state(s), the exit state(s) (those that have no enabled operations).

Step 3: is to identify the source and target states of every operation in the model. To do this, we take every state and every operation that is enabled in that state, and calculate the state that results in applying that operation.

For example, if we derive a state specifying the stack as empty (state \(s_0\)), and a state specifying the stack having one element (state \(s_1\)), then the push operation links \(s_0\) to \(s_1\), the pop operation links \(s_1\) to \(s_0\), and the isEmpty operation links both states to themselves. If modelling exceptions, then applying the pop operation in the empty state will result in the state StackEmptyException.

Example 46: Deriving the stack FSA

As a first example, consider a simple Stack class that we wish to test. An informal specification for this is given in Section Testability of State-Based Programs, and an implementation of that specification is given in Figure 5.2.

Firstly, we want to derive the states of the FSA. Intuitively, we want to consider states with same effect on operations as being equivalent and collect them together into a single FSA state. The equivalence partitioning techniques can be used to derive this. Although equivalence partitioning is an input partitioning technique, the state can be considered as input to any operation that uses it, but it is input that is not passed as a parameter.

Instead of looking at the input domain we look at the states of a module and ask what states can be considered equivalent if we want to find faults in the module operations. We do this for the Stack class in Table 5.1.

State |

Description |

Enabled Operations |

|---|---|---|

State 1 |

An undefined stack |

|

State 2 |

A defined stack that is empty; that is, a stack with no values |

|

State 3 |

A stack that is full; that is, it has the maximum number of elements |

|

State 4 |

A stack that is defined but is neither empty nor full |

|

State 5 |

A stack that is in the |

none |

State 6 |

A stack that is in the |

none |

Table 5.1: States for the Stack module

The initial state of this module is the undefined stack. Alternatively, one could remove the undefined state, and instead specify that the initial state is the empty state. The exit states are the exception states.

The exit states depend on the the specification for the module. For example, popping an empty stack throws an exception, however, an alternative specification of the stack may assume that the stack is not empty when elements are popped, therefore, the behaviour of popping an empty stack is undefined, and cannot be meaningfully tested. In this case, there are no exit states (there is always one operation that can be executed in any state).

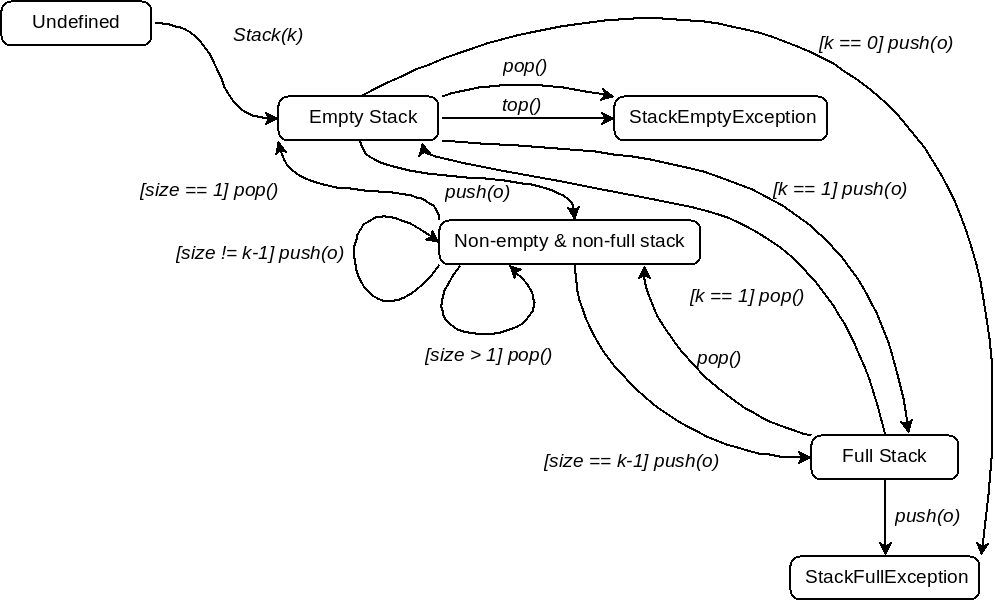

Finally, we derive the transitions between the states. The final FSA for the stack module is shown in Figure 5.2. The transitions of isEmpty and \sf isFull are omitted because they are enabled in all states (except the undefined state) and always loop back to the same state from which they started.

Figure 5.2: Finite State Automaton for the Stack ADT

In this figure, the predicate in the square brackets on the transition labels represent the conditions that must hold for that transition to take place. Note that these are not the preconditions of the operations themselves, but merely the conditions that must hold for that operation to change to the destination state.

Note the push transition directly from the empty state to the full state, with the condition k == 1, is for when the maximum size is \(1\), in which case there is no state in which the stack can be non-empty and non-full. Similarly for the reverse action: popping the stack from a full state, and for pushing onto a stack of maximum size 0, which leads to an exception state.

5.5.2. Deriving Test Cases from a FSA#

Recall from Section Testability of State-Based Programs that the observability and controllability of modules is low due to their hidden information. We discussed that fact that to set up a state for a test input of an operation may require us to execute other operations in the module.

The FSA of a module gives us the information that is required to do so. If the states in the FSA represent the input states that we wish to test, then the transitions that move the state from the initial state to each state represent the operations that need to be executed.

Definition

A path from a state \(s_0\) to a state \(s_n\) in the automaton is a sequence of transitions \(t_1 t_2\ldots t_n\) such that the source of \(t_1\) is \(s_0\) and the target of \(t_n\) is \(s_n\).

The aim is to generate test sequences such that the paths in the automaton are exercised. A test case is no longer a single function call but may require a sequence of operation calls to force the module along a certain path.To derive these sequences, we define traversal criteria for a FSA. Broadly, there are three criteria that we can use:

*State coverage: Each state in the FSA must be reached by the traversal.

Transition coverage: Each transition in the FSA must be traversed. This subsumes state coverage.

Path coverage: Each path in the FSA must be traversed. This subsumes state coverage, but is impossible to achieve for a FSA with cyclic paths.

State coverage is clearly inadequate, because there are transitions in the FSA that will not be traversed, and therefore, operations that will not be tested for the test states that were derived. Path coverage is impossible for FSAs with cycles, so this is infeasible in many cases. Transition coverage is feasible, straightforward to achieve, and it tests every test state that was derived, so this is generally the most practiced traversal technique.

Using transition coverage, we repeatedly derive test sequences starting at the initial node until all transitions have been covered at least once. In some cases, this can be done using one long sequence, but in others, this is not possible; for example, the stack FSA as two exit states, and one of these has two input transitions, which together imply that there must be at least three sequences. Often, it is more efficient to derive many short sequences than a few long sequences.

5.5.3. Intrusively Testing the State Transition Diagram#

Now we an look at intrusive and non-intrusive methods for testing an automaton.

As discussed earlier, intrusive testing, in these notes at least, will mean adding testing code to the module to measure and monitor the internal states of the module as it is tested. The problem with this kind of testing is that it breaks encapsulation.

The points at which to insert testing code into a module are to observe the values of private state variables, observe the values of private operation calls and even observe intermediate states in module operations.

In an object-oriented programming language, this is not as obvious as it sounds because of the problem of inheritance. Consider the class Node for implementing a doubly linked list in the following example.

public class Node

{

private Object _data;

private Node _previous, _next;

}

To observe the state of Node we need to get access to the values of the _data instance variable. However, because _data is an instance of the Object class, this means that we need to ensure that there are operations to access the private state elements of all the objects in the system that inherit from Object[2]; that is, we would need to extend all elements of the hierarchy with testing code. In this case there is a great deal of additional code to write which may well further impact the properties of the entire system.

In languages like C and C++ we can use the pre-processor to compile test code into the executable when required, or to omit the testing code when the program is to be released.

As a result of these problems, systematic intrusive testing is difficult to achieve, in fact, it is often impossible for some languages if we do not have access to the source. Many of the solutions are hacks that give the testers some benefit that outweighs the breaking of the encapsulation.

The best cases are languages that provide semi-private access, such as the protected keyword in Java, or the friend keyword in C++. These give testers the ability to read and write to the variables without changing the program-under-test.

5.5.4. Non-intrusive Testing the State Transition Diagram#

There will be occasions when we simply do not have access to the internal structure of a module or its hierarchy. In this case, or in the case where you simply need to test a module without adding code to a module, then we have non-intrusive testing.

The idea is to test each of the transitions in the testing automaton implicitly by using other operations in the module to examine the results of a transition. Lets start by dividing up the operations in a module as follows:

Transition type |

Description |

|---|---|

Initialisers |

The operations that initialise the module, such as the |

Transformers |

Operations to change the state of the module, such as |

Observers |

Operations to observe the module state, such as the |

Table 5.2: One classification of the operations of a module.

Recall that in the FSA for the stack module, shown in Figure 5.1, the IsEmpty, isFull, and top operations were omitted because they do not move the automaton to a new state. This is because these operations are observers — with the exception of top moving to the StackEmptyException state.

The technique for testing involves deriving test sequences, using initialisers and transformers, to move the automaton to the required state. At each state, observe the value of the module using the observer operations. The only case where the observer operations are not used is in the exception states, because the execution of the module is considered to have terminated. Alternatively, and depending on the programming language, these exception states could be remove from the FSA, and considered as observer behaviour. Many programming languages support the catching of exceptions, thereby allowing the execution to continue.

Example 47: Traversing the stack FSA

For the stack automaton in Figure 5.2, we can obtain transition coverage using the following test sequences:

Sequence |

End State |

|---|---|

\({Stack(0) ; push(o)}\) |

\({StackFullException}\) |

\({Stack(1) ; push(o) ; pop(); pop() }\) |

\({StackEmptyException}\) |

\({Stack(k) ; top()}\) |

\({StackEmptyException}\) |

\({Stack(k) ; push(o)^k ; pop()^k ; push(o)^k ; push()}\) |

\({StackFullException}\) |

in which the notation \({op()^k}\) is shorthand for executing \({op()}\) in sequence \({k}\) times, and \({k > 1}\).

Regarding observer operations, there are several places that these can be tested:

all observer operations could be used to observe the state after a call to any initialiser or transformer operation;

all observer operations could be used to observe the state any time a transition takes us to another state in the FSA; or

all observer operations could be used to observe the state when an FSA state is being visited for the first time.

The first of these seems like overkill, and would lead to a high number of test cases. The second is more reasonable, but considering that each FSA state represents many module states, and each of these is representative of the equivalence class to which is belong, then it seems reasonable to only test the observer operations when an FSA state is being visited for the first time. For the stack example, this gives us the following test sequences, which we instantiate into actual test cases:

Sequence |

End State |

|---|---|

\({\sf Stack(0) ; (isEmpty() == true); (isFull() == true) ; push(o)}\) |

\({\sf StackFullException}\) |

\({\sf Stack(1) ; push(1) ; (isEmpty() == false); (isFull() == true) ; (top() == 1) ; pop(); pop() }\) |

\({\sf StackEmptyException}\) |

\({\sf Stack(2) ; top()}\) |

\({\sf StackEmptyException}\) |

\({\sf Stack(2) ; push(1) ; push(2) ; (isEmpty() == false); (isFull() (top() == 2) ; pop() ; pop() ; push(1) ; push(2); push(3) }\) |

\({\sf StackFullException}\) |

The additional calls to the observer operations, and the checking of their values, is equivalent to adding them into the FSA as transitions from a node to itself.

Remark

Each of the test cases above consists of a sequence of operation calls rather than just a single call.

It is possible that a test case may consist of an equality between two sequences of operation calls, for example,

if such a test for equality can be made.

If operations exist for forcing a module into one of the testing states then this can make testing long sequences of operation calls easier.

5.5.5. Discussion#

The design of state-based systems is an important part of testing. This section has outlined that it is important to define the interface of a module to make as testable (controllable and observable) as possible. Designing for testability is as important as designing to meet requirements, even though there may be conflicts between the two.

Fortunately, many modular design notations that are part of design methodologies resembled FSAs. For example, UML uses state charts precisely for the purpose of specifying and understanding the legal sequences of operations on a class instance, and the states that result from these sequences.

5.5.5.1. Problems with State Based Testing#

Of course there are some problems with FSA-based testing:

It may take a lengthy sequence of operations to get an object into some desired state.

FSA-based testing may not be useful if the module is designed to accept any possible sequence of operation calls. This would result in a FSA with little structure, and require a prohibitively large number of test sequences to cover.

State control may be distributed over an entire application with operations from other modules referencing the state of the module under test.

System-wide control makes it difficult to verify a module in isolation and requires that we identify module hierarchies that collaborate to achieve a particular functionality. Here the collaboration and behaviour diagrams are the most useful.

5.6. Testing Object-Oriented Programs#

Object-oriented programs pose some new and interesting challenges to unit, integration and systems testing. One can view an object-oriented system can be viewed as a modular system, and therefore can test an object-oriented system by applying the techniques already discussed in this chapter. In this case, the modules are classes, and the operations are methods.

However, there are certain properties of object-oriented languages that make testing more difficult than for other imperative languages such as C. In this section, we discuss these differences and present techniques to minimise their impact.

5.6.1. Object-Oriented Programming Languages#

Object-oriented programming languages support a number of features that are aimed at making the design, maintenance and reuse of code much easier. We will not go into detail but will briefly review the major features and start to think about them from a testing viewpoint.

The idea in object-oriented programming languages is that the language provides constructs to support encapsulation and structuring. The key elements that languages such as Java and C++ provide are:

Classes and objects which provide the main units for structuring.

Inheritance, which provides the one of the key structuring mechanisms for object-oriented design and implementation.

Dynamic Binding or Polymorphism, which provides a way of choosing which object to use at run-time.

5.6.1.1. Classes and Objects#

Classes are used as templates for creating objects. The objects do the work while the class just shows you the what sets of objects are active in the program. The common view is that a class declaration introduces a new type while the objects are the elements of that type. Whenever a new object is created it is an instance, or element, of that type. Every object in the class has:

The methods defined by the class; and

The instance variables (or attributes) defined by the class;

There can be any number of objects that are instances of a class, each with different values for their instance variables but no matter what the specific values are the object will still have the attributes and methods specified by the class. This is one thing that we can rely on in testing.

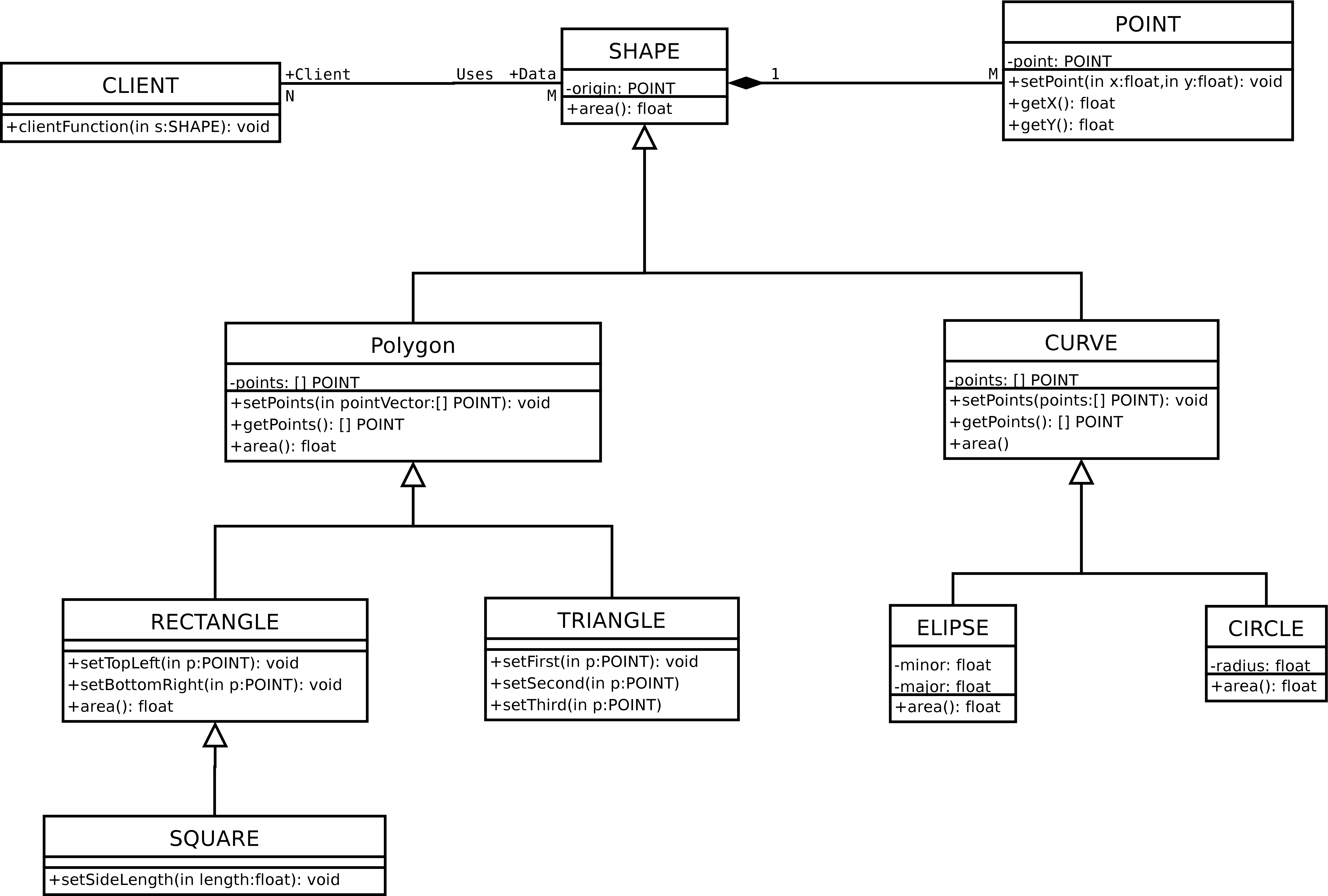

For example, the class Shape in Figure 5.3 defines a type where each object of that type contains a private hidden instance variable origin and a publicly visible method area().

Figure 5.3: Inheritance and polymorphism.

Classes and objects do not present any major obstacles in testing on top of the encapsulation problems in testing modules. In fact, for the purpose of testing a class in isolation, one can consider an instance of a class as simply a record type, in which we have variables bound to values, and a method call to an object as simply an operation call, but with the object as an input/output value.

5.6.1.2. Inheritance#

Inheritance, or generalisation, relationships exist between classes. The parent is the more general class providing fewer methods or more general methods while the child specialises the parent. A child class inherits all of the properties of its parent, but the child class may override operations in the parent and extend the parent by adding more attributes and operations.

In particular, generalisation means that the objects of the child class can be used anywhere that the objects of the parent class can be used — but not the converse. Some languages, such as Java, support only single inheritance, in which a class may only inherit from at most one parent class. Others, such as C++, support multiple inheritance, in which a class may inherit from one or more parent classes. The parent class is called the superclass and the child is called the subclass.

This idea translates to instances as well — every instance of the child class is also an instance of the parent class. Every instance the child class has the same attributes and methods as the parent — however, the child may use a different implementation of a method to that of the parent.

Inheritance is found only in object-oriented programming languages, but does not pose any immediate problems in testing. The techniques presented so far in this chapter are sufficient, however, the most immediate consequence of inheritance is that it effects the structuring of test suites.

5.6.1.3. Polymorphism#

Figure 5.3 shows an inheritance hierarchy with the class Shape as the base class in the hierarchy. Any of the classes that have Shape as the superclass can be used anywhere that Shape can be used. For example, the class Client has a method called clientFunction that takes an object of type Shape as a parameter. However, the actual parameter can be an object of type Shape, an object of type Polygon, an object of type Circle or indeed an object of any type that has Shape as one of its ancestors.

This is the essence of dynamic binding, or as it is often called, polymorphism in object-oriented languages. The combination of inheritance and dynamic binding is extremely powerful for designing reusable and extendable programs. Dynamic binding and polymorphism are both found in some non-object-oriented languages, however, this is uncommon, whereas they are the essence of object-oriented languages.

The combination of inheritance and dynamic binding creates some real headaches for testers, or at least the combination of polymorphism and inheritance must be taken into account.

5.6.2. Testing with Inheritance and Polymorphism#

In object-oriented testing the view is that classes are:

The internal states of the object become relevant to the testing. What this means in testing is that the correctness of an object depends on the internal state of the object as well as the output returned by a method call.

This is the same idea of modules being a state and a set of operations, so classes are thus the natural unit for testing object-oriented programs.

However, once this choice is made then we will need to explore the effects of object-oriented testing in the presence of inheritance/generalisation and polymorphism.

5.6.2.1. Testing Inheritance Hierarchies#

Inherited features require re-testing, because every time a class inherits from its parent the state and operations of the parent are placed into new context — the context of the child. Multiple inheritance complicates this situation by increasing the number of contexts to test.

Ideally, an inheritance relationship should correspond to a problem domain specialisation, for example, from Figure 5.3 a Polygon is a special kind of Shape, a Rectangle is a special kind of Polygon and so on. The re-usability of superclass test cases depends on this idea. Unfortunately, many inheritance relationships do not respect this rule and simply inherit from classes when they want to use library functions.

Which functions must be tested in a subclass?

Figure 5.4 shows a simple parent-child inheritance hierarchy.

class Parent

{

int number()

{

return 1;

}

float divide(int x)

{

return x/number();

}

}

class Child extends Parent

{

int number()

{

return 0;

}

}

Parent is at the top of an inheritance hierarchy, so we derive test cases for this class first, and test it. When testing the Child class, we need to retest the number() method because this has been modified directly. However, we also need to retest the divide() method because it directly references number(), which has changed.

Can tests for a parent class be reused for a child class?

First we need to observe that parent.number() and child.number() are two different functions with different implementations. They may or may not have the same specification (there is no specification for this example); for example, the specification may say that the method must return a number between 0 and 10, but with no constraints as to which number — thus making the specification non-deterministic.

Test cases that are generated for these two different functions, however, are likely to be similar because the functions are similar. Thus, if we minimise the overloading by using principles such as the open/closed principle in our design, then there is a much greater chance that the inherited methods will not need new test cases in the context of the child class.

Clearly, new tests that are necessary will be those for which the requirements of the overridden methods change.

5.6.2.2. Building and Testing Inheritance Hierarchies#

When dealing with inheritance hierarchies it is important to consider both testing and building at the same time. There are two key reasons for this:

the first is to keep control of the number of test cases and test harnesses that need to be written; and

the second is to make sure that we know where faults occur within the inheritance hierarchy as much as possible.

A first approach to inheritance testing involves flattening the inheritance hierarchy. In effect each subclass is tested as if all inherited features were newly defined in the class under test — so we make absolutely no assumptions about the methods and attributes inherited from parent classes. Test cases for parent classes may be re-used after analysis but many test cases will be redundant and many test cases will need to be newly defined.

A second approach to testing and building is incremental inheritance-based testing. Incremental building and testing proceeds as follows:

Step 1: First test each base class by:

Testing each method using a suitable test case selection technique; and

Testing interactions among methods by using the techniques discussed earlier in this chapter.

Step 2: Then, consider all sub-classes that inherit or use (via composition or association) only those classes that have already been tested.

A child inherits the parent’s test suite which is used as a basis for test planning. We only develop new test cases for those entities that are directly, or indirectly, changed.

Incremental inheritance-based testing does reduce the size of test suites, but there is an overhead in the analysis of what tests need to be changed. It certainly reduces the number of test cases that need to be selected over a flattened hierarchy. If the test suite is structured correctly, test cases can be reused via inheritance as well, which provides the same benefits for conceptualisation and maintenance for test suite implementations as it does for product implementations.

Inheritance-based testing can also be considered to be a form of regression testing where the aim is to minimise the number of test cases needed to test a class modified by inheritance.

5.6.2.3. Implications of Polymorphism#

Consider the inheritance hierarchy in Figure 5.3. The implementation of area() that actually gets called will depend on the state of the client object and the runtime environment.

In procedural programming, procedure calls are statically bound — we know exactly what function will be called at compile time — and further, the implementation of functions do not change (well, not unless there is some particularly perverse programming) at runtime.

In the case of object-oriented programming, each possible binding of a polymorphic class requires a separate set of test cases. The problem for testing is to find all such bindings – after-all the exact binding used in a particular object instance will only be known at run-time.

Dynamic binding also complicates integration planning. Many service and library classes may need to be built and tested before they can be integrated to test a client class.

There are a number of possible approaches to handling the explosion of possible bindings for a variable. One approach is to try and determine the number of possible bindings through a combination of static and dynamic program analysis.

Consider the Client class in Figure 5.3. The problem from a testing point of view is to know which actual Shape object gets called at run-time. If an instance of Square is bound to the variable s in clientFunction then we would expect a different result for the area() computation than if that instance Circle was bound to s.

If we instrumented the code for Shape and all of its descendants to reveal the types of the actual objects that are bound to S then we could use that information to determine the subset of the class hierarchy that is actually used by the method clientFunction. The subset can then be covered more thoroughly with test cases. For example, it may be the case that Polygon hierarchy is used by the client function while Curve hierarchy is not. If that is the case the testing clientFunction and the classes in the Polygon hierarchy makes sense but testing the classes in the curve hierarchy makes less sense.

Beware however, this approach is not foolproof and is biased heavily towards the data used to generate the bindings.