Maximum Likelihood Estimation#

Maximum likelihood estimation is by far the better technique for estimating model parameters. Unfortunately it also often requires numerical solutions to solve sets of equations for those very parameters.

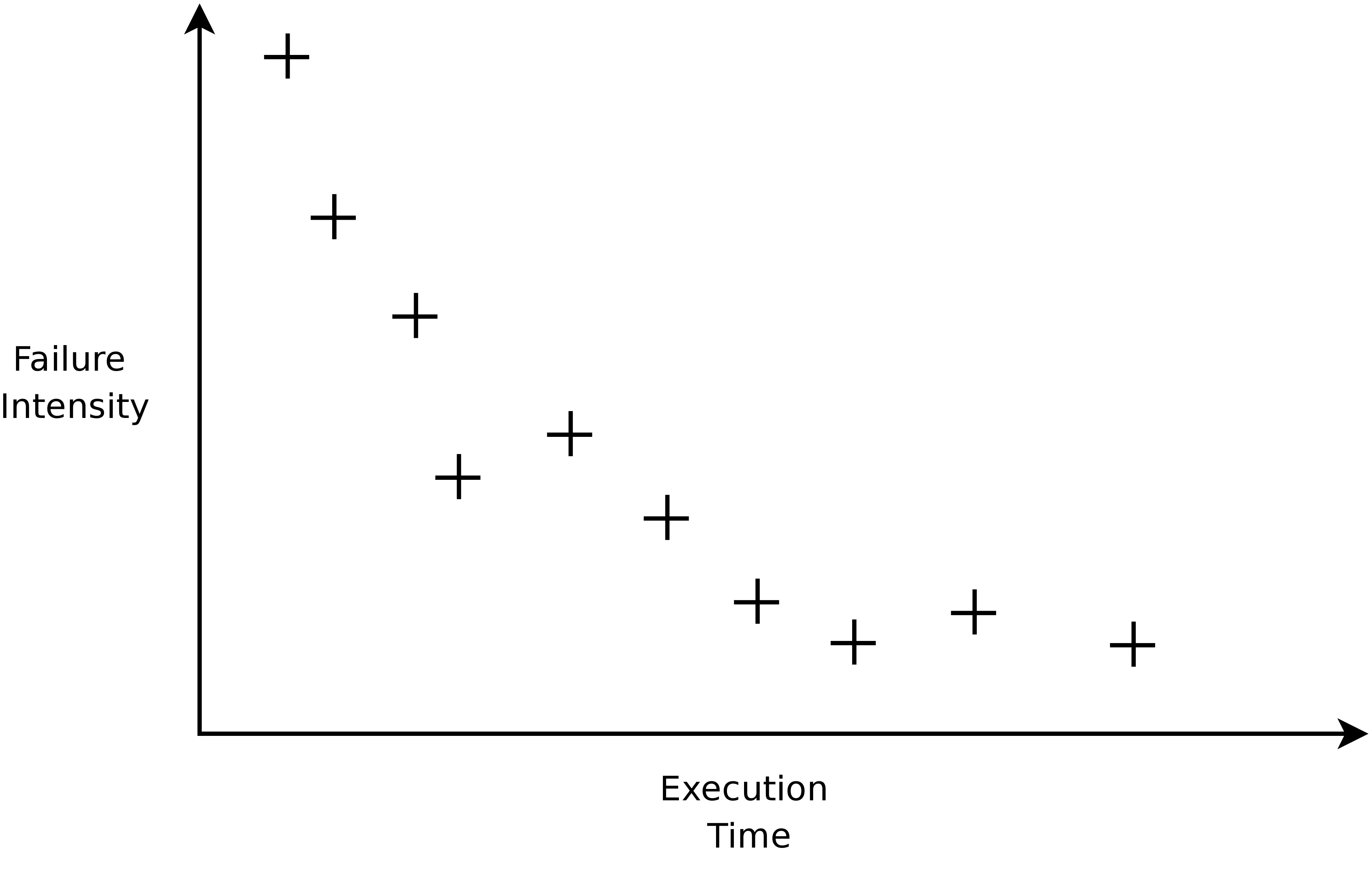

Intuitively the maximum likelihood estimator tries to pick values for the parameters of the basic execution time model that maximise the probability that we get the observed data. For example suppose that we had the failure intensity data shown in Figure B.1.

Figure B.1: Failure intensity against time derived from failure time data for a system.

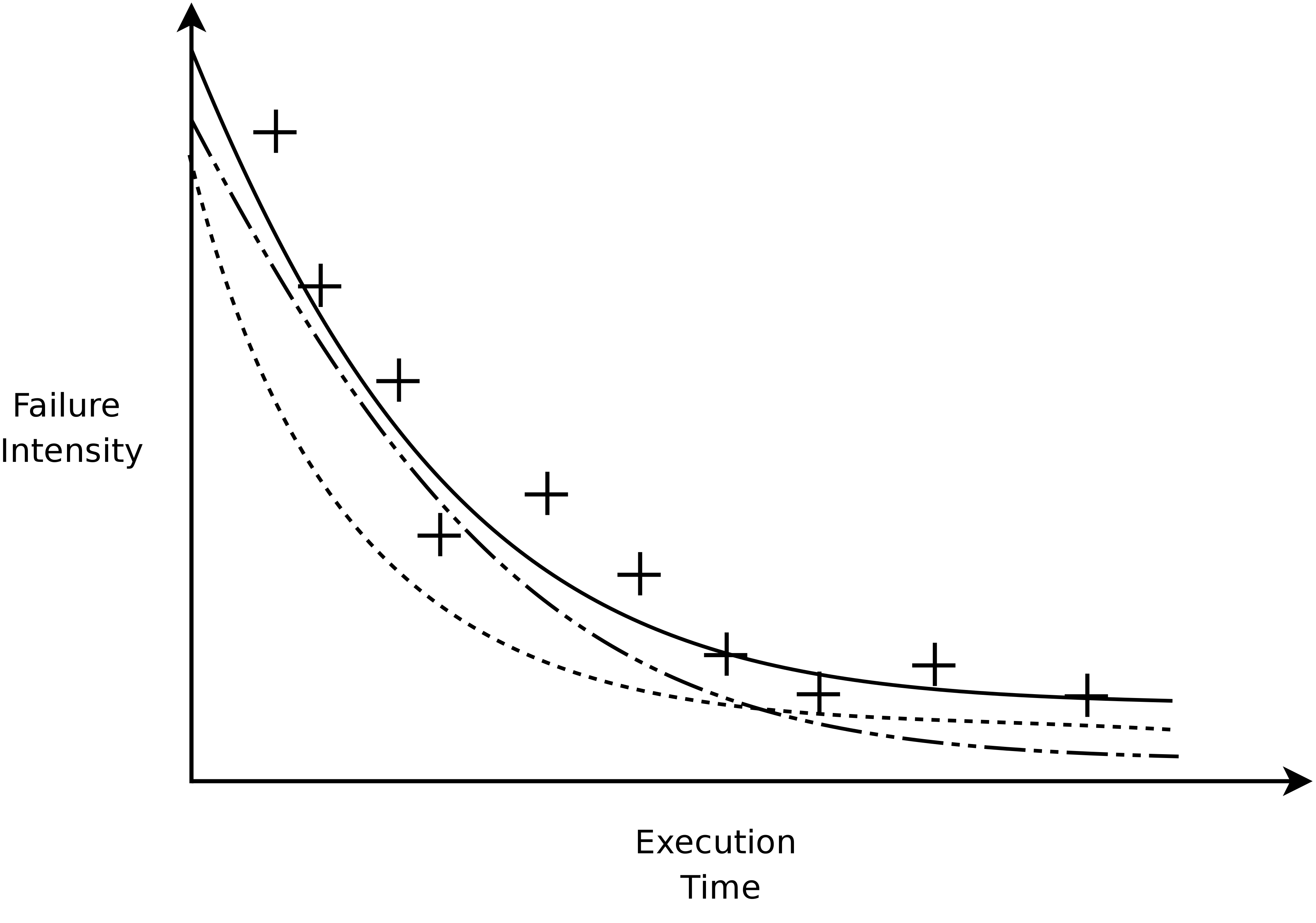

Then we start exploring the parameter space consisting of pairs of values \((\lambda_0,~\nu_0)\) for values that will maximise the likelihood of obtaining the observed values. When we start exploring the values of \(\lambda_0\) and \(\nu_0\) we may find that the curves like something like those in Figure B.2

Figure B.2: Different choices for the parameters result in different curves. The probability of getting the observed data on the curve that we want must give maximum probability of obtaining the data.

To estimate the parameters, maximum likelihood now works as follows. Suppose that we have only one parameter \(\theta\) instead of the two parameters in the Basic Execution time model. Now, if we make \(n\) observations \(x_1\), \(x_2\), …, \(x_n\) of the failure intensities for our program the probabilities are:

To function \(L(\theta)\) reaches its maximum when the derivative is \(0\), that is,

For example, if we have an exponential probability law \(\theta e^{-\theta T}\) with a parameter \(\theta\) and we make \(n\) observations \(x_1\)…\(x_n\) at times \(t_1\) …\(t_n\) then from the exponential distribution, \(\rm L(\theta)\) becomes

An estimate for the parameter is then value of \(\theta\) making

which gives a maximum. In general, when the exponential function \(e\) is involved take the natural log of \(\rm L(\theta)\) and take the derivative. Doing this gives the same value for \(\theta\) as the derivative in. In the case of \(\rm L(\theta)\) we get

and we can easily solve for \(\rm \theta\) to get \(\rm \theta = \begin{array}[c]{c} n \\\hline \Sigma t_i \end{array}\).

The situation with the basic execution time model is not so easy because we have two parameters. To simplify the procedure let \(\beta = \frac{\lambda_0}{\nu_0}\) and let \(X\) be our random variable whose probability density function is \(\rm \lambda_0 e^{-\beta_1 \tau}\). Next, assume that we have been testing for an execution time period of \(T_F\) seconds and have experienced a total of \(M_F\) failures to this point. If we repeat the idea above and take partial derivatives:

we again arrive at our maximum. We again need to take the natural logarithms of both sides to get

The resulting equations that need to be solved often require numerical methods that are outside of the scope of these notes. For completeness, the two estimators are included below.